The changing role of the Ayatollah

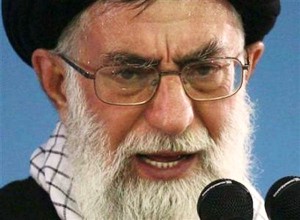

If the thin ice on which a lasting, unprecedented and, perhaps more importantly, uncertain deal between the West and Iran rests fails to break and the assurances of inveterate Iran optimists prove to be correct, many heroes will emerge from the shifting panorama, and deservedly so. It will come as a surprise to many, nonetheless, that one of; if not the most influential of all the players in the Iran-West game is none other than Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamanei. Though it goes without saying that the current Ayatollah draws his inspiration from a completely different set of motives than those of his American and European counterparts, he stands to gain a tremendous amount of support should historic ground be broken within the next several months. The Ayatollah, in spite of deeply critical views of the West, has previously demonstrated that he is willing to tolerate modest steps towards the middle in order to ensure his own personal and political survival, provided that these steps do not infringe on matters of national pride, such as the right to enrich uranium.

That the newly-elected Iranian President Hassan Rouhani adopted a much more moderate posture, and that his administration approached the West with seemingly open arms is well-known and has indeed been commented ad nauseam, therefore making it unnecessary to comment further here. The reasoning, however, utilized to explain such a shift has almost been that the President, his seemingly moderate past, and his Western-educated foreign ministers managed to gain a sufficient amount of trust in order to propose a limited, albeit significant deal that would allow Iran to regain its regional and global influence. Though such reasoning is not entirely without merit, it is important to remember that a similarly moderate candidate, Mir-Hossein Mousav, ran in 2009 under a reformist banner, and lost due to what was largely condemned by Iranians as blatant electoral fraud. What, then, caused 2013 to be different, and why? Given the authority of the Ayatollah in making or breaking presidential candidates, there is only one possible explanation for such a dramatic, ongoing shift: survival. The Ayatollah has shown tremendous, and oftentimes brutal, resolve, both literally and figuratively to maintain himself in power. Despite years of guerrilla warfare and an attempt as assassination that left his right arm paralyzed, the Ayatollah maintained the Iranian presidency throughout the 1980s, before assuming his current role as Iran’s most influential political figure.

Traditionally more of a hardliner, the Ayatollah has flirted with the West in the past, and has similarly given his blessing to politicians with reformist tendencies, though never in as obsequious of fashion as he has with Rouhani. Though many are inclined to believe that such a shift has been born from goodwill, growing dissatisfaction amongst the Iranian populace as a consequence of increasingly suffocating sanctions should be viewed as the principal catalyst. Sanctions aimed at the Iranian economy have decimated the previously flourishing oil and gas sectors, and have paralyzed much of Iran’s banking activities across the globe. On a societal level, the average Iranian has found it increasingly difficult to buy household items and medication, and the inflation rate effecting the Iranian Rial has reached more than 30%, causing it lose the lion’s share of its value. As a natural consequence of significant economic damage, the Iranian populace has shown itself to be increasingly vocal in expressing their disapproval of policies which they view as the source of their misfortune. Neither the election of Rouhani, nor his subsequent actions should, thus, come as a surprise. If a lasting deal is brokered, the Ayatollah will have guaranteed his position in perpetuity, as well as solidified his reputation as devout cleric acting in the interests of his people.

Eric Wheeler