Albania’s EU reforms: good laws, weak implementation

On June 4th, the European Commission recommended that Albania be granted candidate country status.

This has been a long awaited moment for the small Western Balkans country, which has longed to join the EU in an attempt to claim its place within Europe. Albania submitted its application in 2009, and, since then, has made EU-mandated reforms in order to obtain the much-wanted candidate status.

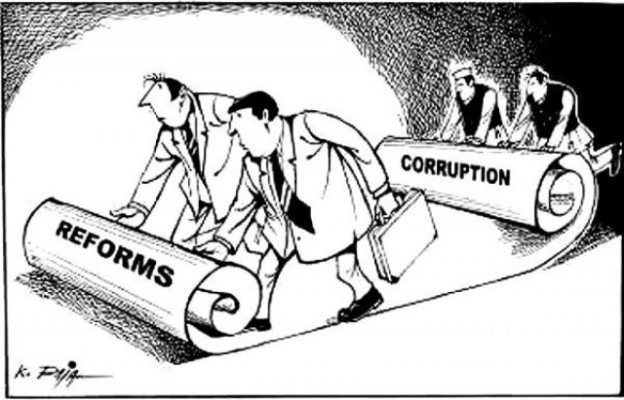

The EU continuously stresses that the main conditions that Albania should fulfill are reforms for the fight against corruption, organized crime, and the reform of the judiciary system. Furthermore, while legislation is not usually a problem, law enforcement and sanctioning are exceptionally defective. The EU, however, mandates reforms which, in their majority, deal with the adoption of new legislation, but in Albania there are enough laws, maybe too many. Nevertheless, the Union recognizes that the country still needs a great amount of work regarding law implementation and sanctioning.

Albania is annually ranked as a highly corrupt country (figures have only slightly improved from 2012 to 2013), and both high level and low level corruption are palpable to anyone that lives in and visits the country. Albania expresses its commitment in the fight against corruption, but the campaigns, seminars, and strategies used in this fight are likely to cost more than corruption itself. Albania has been too focused on anti-corruption measures, while hardly being effective in the sanctioning of these crimes, thus creating loopholes of opportunity for more corruption. An attempt at enforcing sanctioning of corruption crimes was made in March 2013, when corruption offences by high-level state officials were passed to the Serious Crimes Prosecution Office and Serious Crimes Court. The move was criticized by the OSCE, as the institution is not prepared to deal with these cases, and, most importantly, Albania would benefit if corruption would be dealt with by independent and specialized organs. It is also very likely that corruption can only be combatted through a combination of very strong enforcement with a change of mentality in Albanian society, which would span over many decades.

Organized crime is also a serious problem in Albanian society and politics. Although the new government has organized operations, especially against narcotic rings, there is little improvement, especially because, now, the government and the opposition are accusing each other of working with criminal organizations for profit. Geography is also a factor in organized crime, as Albania is a transit country for trafficking to the West, especially to Italy. However, the real issue is that it is very difficult for a disorganized state to fight against organized crime, especially when the elements of politics and crime have been in a symbiotic relationship for such a long time. It seems that the new government is making an effort in changing this damaging relationship; however, the problem in Albania is less the organized crime and more the disorganized state, because an inoperative state does not have the capacity of hindering and fighting organized crime.

Regarding judiciary reform, Albania has worked with the Venice Commission to improve the accountability, efficiency and transparency of the system. However, there has not been much improvement. The judiciary has been called “the weakest link in Albania’s fragile system of separation of powers”, and it remains politicized and clientelistic, behaving like an untouchable corporation and using its independence as an armor. On the one hand, reform of the judiciary is essential, but on the other hand, its independence must be respected, making for a catch-22 situation.

Furthermore, any attempt at reform is met with backlash by the opposition, leading to a very delicate state to manage, as reforms cannot be made only by unilateral decision. Interestingly, both parties, which have exclusively dominated Albanian politics since the fall of communism, are extremely in favor of European integration; nevertheless, there is constant tension between them, making it very difficult to find any consensus on what is fundamentally the same aim and agenda for both parties, that is, EU accession. This lack of dialogue and constant conflict between government and opposition has, many times, hindered reforms or even made them invisible. The EU has picked up on this, and is now repeatedly calling for “the finding of a common language” as if it were a reform, even a condition, in itself.

The final decision on whether Albania will be granted candidate status will be made on June 26th-27th, when the European Council will hold its next summit. While the Albanian political elite, citizens and intellectuals all state that another veto this year would be heavily disappointing, it is also possible to look at the whole process through a more positive perspective. Even if Albania does not become a member state, the reforms it is trying to make in order to join the EU are very valuable in themselves. In the long run, these changes will modernize a troubled country with a very difficult past.

Kristina Lani