Lobbying in the EU and in Spain: an overview

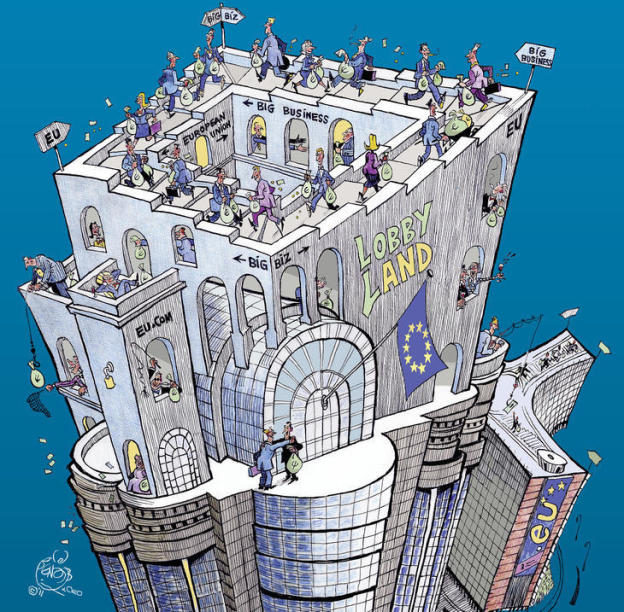

Figures make an impact for those interested or not in European affairs. Lobbying is a billion-euro industry in Brussels.

A notable article was written in The Guardian, a British newspaper, about this issue: According to Corporate Europe Observatory, a watchdog campaigning for greater transparency, there are at least 30,000 lobbyists in Brussels, nearly matching the 31,000 staff employed by the European commission and making it second only to Washington in the concentration of those seeking to influence legislation. Lobbyists usually sign a transparency register run by the Parliament and the Commission, though it is not mandatory to do so at the moment.

The term “lobbying” refers to the activity aimed at influencing policy and legislative decisions based on the interests of certain groups of people, institutions or companies. Etymologically the origin of the word comes from late eighteenth century England. Access of citizens to the House of Commons was forbidden, so meetings with Members in hallways or in the waiting rooms of Parliament (which were known as lobbies) took place.

According to the Commission, the stakeholders can be divided into non-profit organizations (associations, European, national and international federations) and profit organizations (legal advisers, public and private companies and consultants). The first ones are professional organizations. The second ones are persons who often act for others to defend their interests. It was not until a few years ago when the debate around the regulation of lobbies arose in Europe. The reason was the importance that lobbies had gradually acquired in decision-making in the European Union.

The EU has adopted two kinds of measures regarding lobbies. First, providing information about lobbies to anyone interested (citizens, political parties, NGOs…) secondly, there is a Code of good practices that lobbies must abide. Over time, the Commission and Parliament have attempted to address the issue of transparency and registration of lobbyists. The European Parliament launched its register of interest groups in 1996; the European Commission, meanwhile, started its own voluntary registration in June 2008. Already in 2011 an “Agreement between the European Parliament and the European Commission on the establishment of a Transparency Register for organizations was signed and people who work on their own involved in the development and implementation of policies of the European Union” was signed.

Until now, more than 6000 organizations have voluntarily enrolled in the Transparency Register of the European Union established in 2011. EU authorities think that more than 25% of the groups of interest that actually operate in their institutions are still out of this register.

As far as lobbying in Spain is concerned, the constitutional regulation is unclear and dispersed. On the one hand, Article 9.2 CE manifests as a commitment of public authorities “to promote the conditions for freedom and equality of individuals and groups in which they belong are real and effective” and “remove the obstacles that prevent or hinder their fulfilment ‘facilitating’ the participation of all citizens in political, economic, cultural and social life”.

This article allows for the creation of groups that could facilitate stakeholder participation in decision-making and public regulation. Articles 7 (which refers to the general interest of trade unions and employers), 23 (which regulates fundamental right of participation), and 103.3 (which refers to the guarantees of impartiality of officials) are also normative benchmarks.

Spain gets poor results in “three crucial aspects” of lobbying: transparency, integrity and equal access. In a report launched by Transparency International, an NGO, Spain was detected to suffer from both “weaknesses in the activity of lobby” and “loopholes and inadequate legislation”. The report also states that “in Spain there are no regulations which ensure in all cases know who influences how, on whom, with what results and how does financial means”. The reasons for these poor results may be the lack of registration of lobbyists, the lack of obligation to report their activities by those who are lobbying and the inexistence of bodies that monitor and control their activity.

Although transparency in lobbying in Spain is a disputed matter, the current situation has changed to some extent. Some positive aspects deserve mention; for example, regional parliaments are going beyond the law and offer more information on their websites about these kinds of activities and some parliamentarians are progressively showing their agenda and meetings with lobbies and other groups.

The issue of revolving doors (“puertas giratorias”, in Spanish) is also subject to profound criticism. There are obvious examples of bad practices that have taken place in Spain. Practical examples of “bad practices or unethical practices” due to the action of lobbies, where handled such as the closing of Garoña services, licensing of DTV, or the law of intellectual property.

We are living in times where transparency is not negotiable anymore. Therefore, political authorities should show clear information to their contacts in relation to each measure or public policy and report their agendas. At the same time, lobbyists should make an exercise of accountability of their activities for those people who are interested in getting more information.

Manuela Sánchez Gómez