The difficult struggle for women’s educational rights in Pakistan

Education has been of central significance to the development of human society. The international community’s commitment to universal education was first set down in the 1984 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

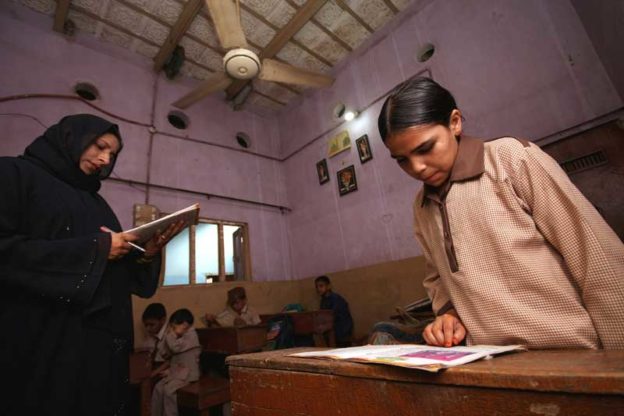

In Pakistan, particularly in rural and sub-urban areas, women are situated largely at the bottom end of the educational system. Traditionally, it is assumed that women are limited to their homes and men are the breadwinners of the family. In this situation, education can play a vital role in enhancing the status of women and placing them on an equal footing with their male counterparts and also increasing women’s ability to secure employment in the formal sector.

Women’s education is so inextricably linked with the other facets of human development that to make it a priority is also to make a change on a range of other fronts, from the health and status of women to early childhood care; from nutrition, water and sanitation to community empowerment; from the reduction of child labour and other forms of exploitation to the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

Education is a critical input in human resource development and is essential for a country’s economic growth. The recognition of this has created awareness on the need to focus upon literacy and elementary education programs, not only as a matter of social justice but also to foster economic growth, well-being and social stability.

Educational rights play an important role in the international agenda. After the aforementioned 1984 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child was signed in 1989. This commitment was again reaffirmed by the world leaders one year later at the World Summit for Children. In September 2000, The United Nations Millennium Summit focused on the issues of gender inequality and addressed the problem in its two Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Some figures about education in Pakistan must be explained to understand the complicated situation in the country. Firstly, Pakistan has the world’s second highest number of children out of school, reaching 5.1 million in 2010. Secondly, two-thirds of Pakistan’s out of school children are girls, amounting to over 3 million girls out of school. While 8% of men are not in the labour force, the figure for women reaches a dramatic 69%. Thirdly, one of the most important concerns to international authorities is education’s public expenditure. As a matter of fact, Pakistan spends 7 times more on the military than on primary education.

In the last few years, we have witnessed the rise of new technologies that can play a fundamental role in the struggle for educational rights in the Asian country. Mukhtar Mai Women’s Organization and BBC Diary of a Pakistani Schoolgirl are two clear examples of this.

Established in 2003, Mukhtar Mai Women’s Organization (MMWO) is led by Mukhtar Mai, internationally known for her struggle for the protection and promotion of women’s rights. In April 2007, Mukhtar Mai won the North-South Prize from the Council of Europe.

Mukhtar Mai Women’s Organization is the champion defender of women’s rights and education in the Southern region of Punjab Province, Pakistan, a region with some of the world’s worst examples of women’s rights violations. This organization provides assistance to women through telephone and the Internet.

Blogs have become a powerful tool to defend women rights as well. Pakistan is a country where freedom of expression is limited. In this context, the blogosphere is an essential tool for women to express their views, their frustration and their complaints about Pakistani reality. The best know example of a blog’s success is ‘BBC Diary of a Pakistani Schoolgirl’.

I wouldn’t like to finish these few lines without mentioning some ideas about the measures taken by the Government to face this situation. Despite the Government’s commitment to provide free and compulsory education to all children aged 5-16 years, Pakistan faces major challenges to universal access as well as the relevance, quality and efficiency of the education system. A key achievement –although still insufficient- was the Government’s commitment to increasing the national budget allocation for Education from 2 to 4 per cent of GDP by 2018, in order to accelerate progress towards the MDGs for Education. These increased funds will provide opportunities for improved access, better quality and addressing the equity issue. The countrywide ‘Every Child in School’s campaign, launched with Unicef’s collaboration, reached out to the most remote districts in all provinces and areas to encourage school communities (teachers, students, parents, and local stakeholders -including religious leaders-) to actively work towards enrollment and retention of out-of-school children, particularly girls, and to increase the demand for quality education systems.

Manuela Sánchez Gómez